“Your pardon,” said Keegan te Fliss, “but is there time for me to see what the Director offered to show to me?”

Gredin had almost forgotten the historian, seated apart from the group as he was, and she had entirely forgotten Wyve’s offer.

Cirin said, “I imagine the Voice would like to return to the enclave without delay. What if I walk there with her and First of Memory, and Burlon and Gredin can wait here to escort Keegan back, once Wyve has finished? After all, Keegan will need someone to help him speak with Wyve.”

The offer caught Gredin off guard. She knew that Burlon could easily fill the interpreter’s role, but Cirin had singled her out to stay, and it was an appealing compromise. In fact, she was beginning to suspect that Cirin te K’lar was a cannier man than she had first assumed. His use of Tetralanna’s title had been a tactful choice, as was his pairing of her with Sill te Torr, who also wore a First.

It was no real surprise, then, when Tetralanna rose from her bench, gave a gracious nod to the Director, and made her way toward the office door. “Gredin, translate for the historian, but don’t pester the Director with questions,” she admonished. “And don’t linger. It must be nearly time for evening meal. I will see you in our chambers afterwards. The two of us have matters to discuss.”

That had a dire sound to it, but Gredin’s spirits rose at the thought of spending time in the Director’s office, however briefly, without having to worry over Tetralanna’s reaction to each word and look. It might be an uncharitable thought, but it was an honest one. She did truly want to make a positive impression on Tetralanna, but it was a relief not to be faced with the woman’s nervous mistrust of everything around them.

As soon as Cirin, Sill and Tetralanna were gone, the Director turned to her. “And so, you are now permitted to have a name?”

“Gredin,” she said promptly. “Gredin te Balamont.”

“You speak Prettian quite well, Gredin te Balamont.”

“The Traders have been kind enough to teach it to me, ever since I was young.”

That won a bark of laughter from Burlon. “You’re still young,” he pointed out, and added, “Be careful with this one, Wyve. She’s scarcely out from under the care of her Guides.”

“Guides?”

“The people who raise the babies and children.”

“Ah,” Wyve said. “Her mother and father.”

Burlon stared at him. “No, her Guides, Beda and Ingarra. The ones who had the daily care of her.”

Wyve opened his mouth as if to say something more on the topic, then simply closed it again, although not before Gredin had a disconcerting glimpse of the teeth, broad and flat, that rested in a gleaming curve just within his pale-grey lips.

“We didn’t think we’d be able to bring Gredin along on this trip, despite her ability to speak your language,” Burlon elaborated, “because she wasn’t yet mature enough to leave her House. It was a near thing – a matter of less than a sector.” He grimaced. “But, except for our Traders and Travelers, she’s the only one who has ever showed an interest in learning Prettian or Tradetalk. So here she is.”

“Come here to my desk,” Wyve invited, and beckoned for the three of them to gather around the glass tabletop.

When Gredin walked up to Director’s table, she was surprised to see that the tall glass vase sat on a large plate of glass, and that it was not vacant at all. Seen from this new angle, an image glowed within the column: a blue and green sphere, rather like one of her stones. While she gazed at it, a silver speck appeared from behind the sphere and began to cross in front of it at a sedate but steady pace. And the plate beneath displayed several concentric rings of numbers that flickered and changed.

The Director must have noticed her gazing at it, for he gestured at the column and plate. “This is my chronorb.”

The word meant nothing to her, but she smiled and said, “It is very pretty.”

That caused the Director to chuckle. “I suppose it is. But that is not why I have it here. The chronorb measures time, and shows how Tradepoint circles our homeworld. You see the blue and green ball?”

She nodded.

“That is Prettig. Prettig is our planet, as Venna is yours. This is how a planet appears, when viewed from space.”

She glanced at Burlon uncertainly, who looked amused as he said, “I wish you good fortune with your explanation, Wyve. She knows Venna to be a vast, flat land, varied only by mountains and seas. Certainly not a ball.”

Wyve nodded, but he persevered. “You see that little silver speck?”

“Yes,” Gredin assured him.

“That is Tradepoint.”

It seemed a most peculiar thing to say, but it was certainly not her place to appear to doubt the Director’s words.

“Rather,” he amended, “it represents Tradepoint. At this moment, we are traveling around Prettig, just as that speck is traveling around the blue and green ball. You have seen the countback clock in your enclave, yes?”

“The lighted numbers over the enclave door,” Burlon prompted.

“Yes,” Gredin said, remembering the numbers on the display.

Wyve took up his narrative again. “Each time that Tradepoint completes a circle around Prettig, the numbers on the countback monitor grow smaller by one. That happens fifty times in a single sect, as Vennans and Prett measure such a thing. The number on the countback monitor begins at two thousand orbits, when a tradeteam arrives. When that number is reduced to zero, forty sects later, a tradeteam is required to depart from Tradepoint.”

His words flowed over her like water. She recognized most of them, but the sense of what he was trying to explain to her ebbed and flowed. She nodded and smiled, resolving to beg Burlon to tell her what it really meant, later. For now, she knew that the chronorb was a pretty thing, and that it reminded Wyve of his home, and that the delegation’s time on Tradepoint was limited. But she had already known that. They were going home in just a few days. She needed no column of glass to tell her so.

To her relief, Wyve turned away from the chronorb. “Ask Keegan to show me what he wrote during our meeting, would you?” he requested.

She turned to the historian. “The Director would like to see your writings, if you have no objection.”

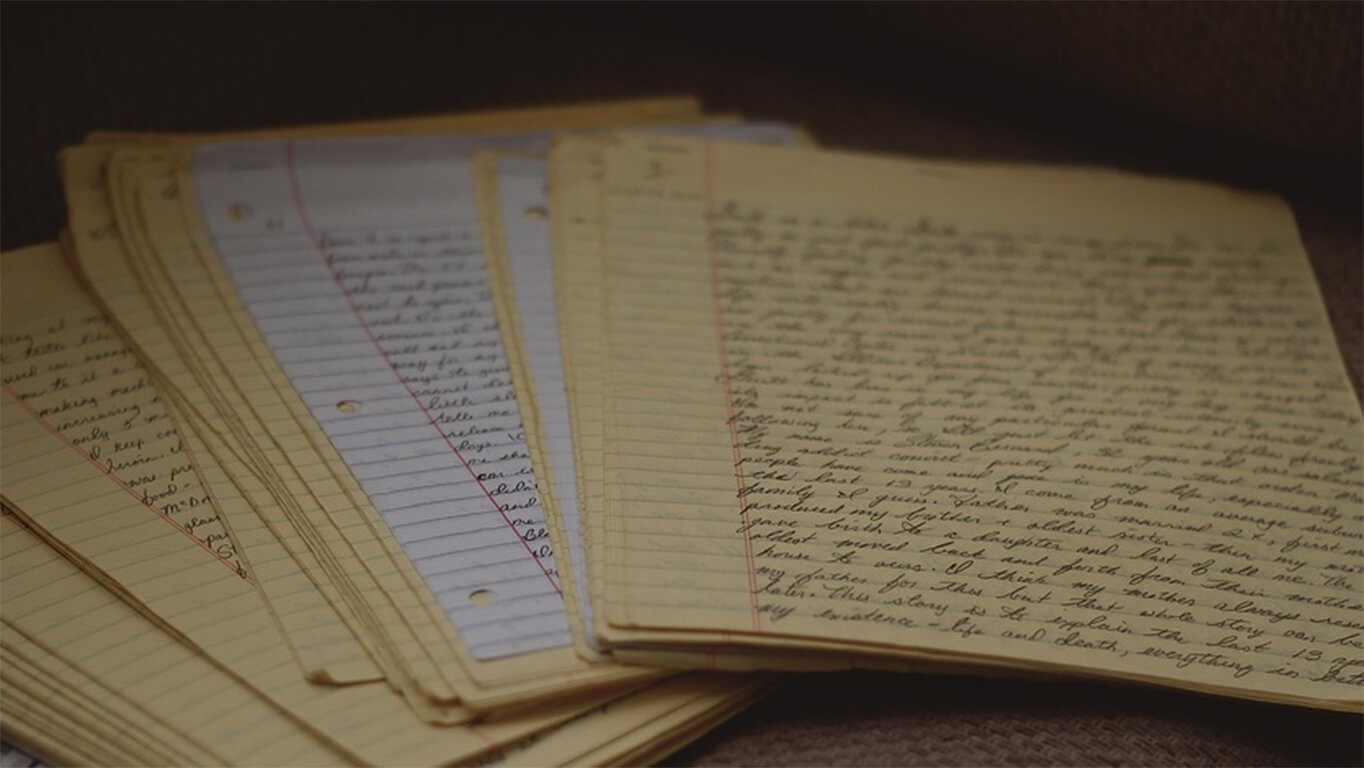

Without hesitation, Keegan opened his notebook and set it within easy reach.

The Director extended one of his big hands over the notebook, then flexed his fingers.

Gredin bit back a gasp as the roughened skin at the end of each finger parted slightly, allowing a slender tip to emerge. The unprotected tips were pink and uncalloused, and Wyve utilized those tips with delicacy to turn the topmost page, and then the next. Peering at the notebook, he murmured, “Intriguing. I was unaware that Vennans had such an intricate form of written language. Until now, I have only seen your number system, on the forms your Traders fill out for the station.”

Gredin translated that explanation for Keegan.

Wyve pointed at the little cloth roll in Keegan’s hand. “Is that where he keeps his—” And he used a Prettian term that meant nothing to her.

“Your pardon,” Gredin said. “I don’t understand that word.”

“The thing with which he makes these marks.”

She nodded and turned again to Keegan. “He would like to see your reed pen and, I suppose, your ink vial.”

Keegan unpacked them from the roll.

“Ask him,” Wyve said, “to make the marks that represent his name.”

“Keegan, the Director would like you to write ‘Keegan te Fliss’ on the page.”

Keegan wrote out his name and then said it aloud, pointing to each word in turn.

Wyve seemed surprised. “It is what, that little word in the center?”

Gredin pondered how best to explain. Pointing, she said, “The first word is ‘Keegan,’ which is his name, just as I am called Gredin and you are called Wyve. And the last, ‘Fliss,’ is the name of his House. The little one between…I suppose you would render it as ‘of.’ You are Wyve of Tradepoint. He is Keegan of Fliss.”

“‘Of,’” Wyve said on a note of quiet wonder. “Imagine. I have heard Vennans speak their names for many a sectora, here on Tradepoint, and yet I never realized… Well! I consider this meeting to be a success, for I have learned something new about you all.” He nodded toward Keegan. “Tell him to watch, now, and he will see how his name appears in Prettian.”

“The Director says that he will show you how he writes your name in his language.”

But what Wyve demonstrated was far more surprising than that. He used no paper, no reed pen, no ink. Instead, he touched a particular spot on the tabletop and the surface came to life, glowing softly as it showed a number of small rectangles. “Each of these shapes represents one of those benches,” he said, with a nod toward the room in which they stood. “I have not erased the settings from our meeting yet, so you can see which benches sat empty and which were occupied. Gredin, you stood there,” he said, pointing, and she saw a cluster of lighted symbols glowing behind that particular rectangle.

“Is that my name?” she asked.

“No,” Wyve said, with a rumbling chuckle, “because, as you may recall, you would not tell me what it was. What I have written there is ‘translator.’ But tell Keegan to look here, at his bench, which we moved. This is his name, as best I understood it at the time, and a further notation that he had come in the role of historian.”

When Gredin translated Wyve’s words, Keegan leaned in closer to peer at the glowing symbols. “May I copy those down?” he asked.

Gredin conveyed the request, which Wyve granted with apparent good cheer. “Of course. I thought it might please him to do so.”

It was all a puzzle to Gredin. She understood how ink could make a mark upon paper. She was far less sure how Wyve had created the symbols that glowed on the surface of his desk, and equally surprised when, after Keegan finished copying, a further touch from Wyve caused all of the symbols to vanish.

But she made no comment. It was not the first thing about Tradepoint to astonish and bewilder her, and she doubted whether it would be the last.